Microscopic Problem, Macroscopic Consequences

How The Coronavirus is Impacting the World Economy and the Political Stage

By Ryan Tierney ’20

On January 20th of this year, global crude oil prices were at relatively normal levels, averaging around sixty four Brent U.S. dollars per barrel.

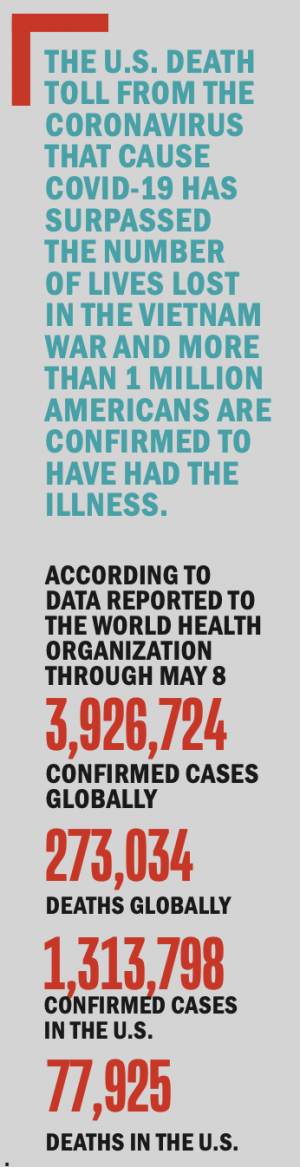

At this time, there were roughly 9,000 reported cases of the novel coronavirus across the world, mostly located in China.By April 20, after global coronavirus cases had grown to nearly two and a half million, oil prices across all continents had dropped to unprecedented new lows, with some U.S. crude oil prices dipping to negative values. The International Monetary Fund, in an estimate that it admitted “may actually be a more optimistic picture than reality produces,” has predicted that world GDP will decline by 3% as a result of the virus. To put that in perspective, that is nearly three trillion U.S. dollars of commerce ceasing to exist. In three months, the coronavirus has killed hundreds of thousands, including 69,500 here in the U.S. as of May 4, and brought the global economy to its knees. As cases continue to spread rapidly across the world, the way forward is uncertain.

This problem has left many governments across the world scrambling to curb the virus’ spread and provide aid to their citizens and businesses. Earlier in the year, China imposed strict lockdown policies on its citizens, and since then, other countries like India, France, and Italy have followed suit. The United Kingdom, which has been in lockdown since March 23, released a 400-million-pound economic stimulus package to help COVID- affected industries and pledged 200 million pounds in aid to help developing countries combat the virus. Even the Afghan government and the Taliban, who are still actively fighting, are taking measures to prevent the disease (although experts believe that Taliban efforts are mainly for public relations).

Here in the United States, no national lockdown has been put into place. The U.S. Navy sent hospital ships to California and New York, the CDC has been releasing federal guidelines for personal disease prevention like social distancing, and the Federal Reserve Board has been actively monitoring the economy too.

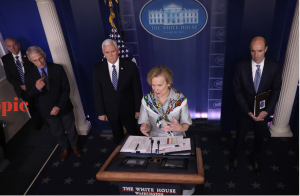

Members of the federal coronavirus task force, like Dr. Anthony Fauci, a Jesuit- educated, Regis High School (New York City) and College of the Holy Cross alumni and director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and response coordinator for the White House Coronavirus Task Force Dr. Deborah Birx, have become public figures as they have continued to advise the White House and brief the American people on the status of the virus.

At the end of March, Fauci said regarding the stay at home recommendations, “We’re sensitive to the idea that the economy could suffer, but it was patently obvious looking at the data, that at the end of the day if we try to push back prematurely, not only would we lose lives, but it probably would even hurt the economy.”

To relieve economic decline, Congress has passed four coronavirus stimulus packages with a total price tag of nearly 2.8 trillion dollars. These packages, which Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has described as a way to “help the people of this country weather this storm,” have promised millions of dollars in loans to small businesses across the country and “stimulus cheques,” averaging about $1,200 dollars, for countless American households. But President Donald Trump, in an effort to keep “the cure [from being] worse than the problem itself,” (a phrase which he first coined in a tweet on March 22) has given states much of the responsibility to enforce regulations and provide relief.

In Colorado, specifically, many measures have been taken. Some public-school districts announced temporary closures for in person classes as early as March 13, and on March 26, Governor Jared Polis announced a state- wide stay-at-home order to contain the virus. Later, on April 3, metro area school districts announced that the closures would continue for the rest of the academic year, and on April 20, Governor Polis extended this order for all Colorado schools. Since then, Polis has begun to reopen Colorado under the “Safer at Home” plan, which was implemented via his executive order on April 22. At the same time, Mayor Michael Hancock extended Denver’s stay-at- home order through May 8, and on May 1 he issued an edict requiring masks to be worn in all public places throughout the city.

In addition to these steps, the Colorado Department of Human Services expanded its coverage for the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program, better known as Colorado Works. Many states have implemented similar regulations, but others have issued far more lax rules. The Archdiocese of Denver, following Polis’ social distancing protocol, suspended all church services through May 8. However, Florida, Kansas, and some other states still allow for large church gatherings, and others like Missouri didn’t implement any sort of restrictions until April.

State governments have also had to use their budget to obtain medical equipment for their hospitals. Colorado is no exception, as Governor Polis announced on April 1 that the state government would also be purchasing millions of masks and gloves from various manufacturers across the world. But as these supplies become increasingly in demand, states have found themselves competing against each other, and some entities of the federal government like FEMA, to get supplies. For example, on May 1 Governor Polis announced that he had ordered 100,000 COVID-19 tests from South Korea but kept it secret due to interstate competition. As he said in his May 1 press conference, “We’re worried about [the federal government/other states] cutting [the supplies] off in the supply chain or Customs. We don’t want to increase the risk to Coloradans by having these things taken out from under them.”

Since the roll-out of the four stimulus packages, technical issues and glitches have abounded, preventing families from receiving their federal stimulus checks through direct deposit. In addition, an overwhelming demand for small business loans, as well as a controversial use of $365 million of designated small business loan funds for publicly traded companies, left the program virtually out of money within two weeks of

the third stimulus package. The program received relief on April 21, but not until many companies were forced to lay off workers, driving the U.S. unemployment rate to nearly 20 percent (the highest rate since the Great Depression). Even the U.S. Navy was thrust onto the world stage when the captain of the USS Theodore Roosevelt, a nuclear carrier currently anchored in Guam, was fired after releasing a letter detailing the grave COVID-19 situation aboard his vessel, where at least one crew member has since died.

Controversy has swirled around President Donald Trump’s rhetoric on Twitter and during press briefings, which have been the subject of criticism from both sides of the aisle. For instance, on April 12, the president retweeted a tweet to his 79 million followers from former congressional candidate DeAnne Lorraine, which included the hashtag “#FireFauci,” referring to the White over the desk and said, here are the data, take a look. He looked at them, he understood them, and he just shook his head and said, ‘I guess we’ve got to do it.’”

House Task Force’s leading infectious disease expert and Dr. Anthony Fauci. This prompted anti- lockdown protesters, including some in Colorado who stood up to medical professionals who were counter- protesting, to include “Fire Fauci” in their signs and chants. Trump, when asked by reporters during a press briefing if he noticed the “#FireFauci” hashtag before he retweeted it, responded, “I notice everything. I retweeted somebody. I don’t know. They said ‘fire.’ It doesn’t matter. It was someone’s opinion. … I think he’s a great guy” and “I like him, he is terrific. Not everybody is happy with Anthony, not everybody is happy with everybody.”

When asked if he would listen to Dr. Fauci and Dr. Birx if they told him the country is not ready to reopen by May 1, President Trump said, “I will certainly listen” and he added that he has “tremendous respect,” for them both, adding, “I’m never saying bad about these people.”

Dr. Birx told reporters that the president “has been so attentive to the details and the data, and his ability to analyze and integrate data has been a real benefit during these discussions about medical issues.” Fauci added, “We argued strongly with the President that he not withdraw those guidelines after 15 days but that he extend them, and he did listen,” Fauci said. “Dr. Debbie Birx and I went into together in the Oval Office and leaned

The president has received criticism from his labeling of COVID-19 as the “China virus” (first in a press conference on March 19 and in multiple tweets since then), as well as his April 17th tweets to “LIBERATE MICHIGAN,” “LIBERATE MINNESOTA,” and “LIBERATE VIRGINIA, and save your great 2nd Amendment!” These tweets seemed to further encourage the anti-quarantine protests in states across the country. The tensions have been especially high in Michigan, where armed protesters stormed the Michigan statehouse on May 1.

Stateside, many political implications of COVID-19 have already become apparent. Voting rights and accessibility, which were a hot topic on the Democratic primary campaign trail, are once again being called into question ahead of the November elections as states move to replace in-person voting machines with mail-in ballots. Proponents of universal healthcare have also used the virus as a platform, comparing the interstate competition of U.S. hospitals for supplies to the more streamlined approach of the UK’s National Health Service. The virus has even brought questions on a constitutional level, as many U.S. citizens, media outlets, and politicians try to determine the federal and state government’s role and power in a national emergency.

On the global stage, it is hard to predict how these internal conflicts will influence the United States’ power. Some analysts argue that the response to COVID-19 might become a “Chernobyl moment” for many countries and could even signal a loss of global status. For the United States, this vacuum could lead to an increase in aggression and influence for autocratic countries like China, which has increased strategic bomber sorties over Taiwan and the South China Sea in the past month. However, others argue that U.S. power loss will be offset by China’s and Russia’s lack of transparency, leaving its status intact. Nevertheless, the problem of COVID-19 is far from over, and as the weeks wear on, the impact it has on the world economy and geopolitical relations will continue to grow.